Success, Mushrooms, & Eagles vs. Quetzals

How we judge our success when working with others | What can mushrooms teach us about migration | The American eagle and the Guatemalan quetzal

Hello Friends,

It’s been a little while. I was hoping to be in touch sooner, but the last few weeks have been full of work-related travel, getting kids ready for a new school year, and the general business of life.

Today I’d like to share three little things rather than one long thing. I hope you find value in at least one of the three ideas in this post.

Inputs vs. Outputs: A Personal Reflection on Measuring Success

As my children have gotten older and as I’ve taken more leadership responsibilies at work, I’ve come to realize that I have little influence on the choices others make or on group-level outcomes. I can’t gaurantee that my children will choose what I think is best for them. And I can’t be sure that the teams I work with will perform exactly as I expect them to.

This is obvious to anyone involved in a collective task. It’s also hard for me, and frequently leads me to feel like I’ve failed as the person in charge. Life is showing me that I’m much more of a control freak that I’d like to admit.

There’s a lot written about this, of course. It’s called parenting in families, and management in organizations. And smarter people than me offer good books on both subjects. I don’t pretend to have anything that useful to say about it.

But some time ago I came to a simple realization that’s removed a lot of the stress involved when I’m “in charge” of any collective (team, family, organization) task:

I can only measure success by outputs when the task depends entirely on me.

When the task depends on the input, effort, or agency of others, I can only measure my success by my inputs.

This doesn’t mean that I shouldn’t care about the outcome of what my kids or my team do, or even that it shouldn’t hurt when the outcome is undesirable. It’s just that the outcome isn’t a good reflection of my contribution. Some bad parents have good kids. Some great parents have troubled kids. Some good bosses don’t achieve all their team objectives. And some bad bosses are part of teams that still perform well. Because humans are complicated, the inputs we put in when working with them don’t always cause desired outcomes.

But we can take comfort in knowing that we did our best with the inputs that were up to us. And so, when it comes to my family, friends, or coworkers, I’m trying to measure success by what I put in to the relationships involved. Do I genuinely love and care for the people around me? Do I take sufficient time to understand and provide guidance or training? Am I available to troubleshoot problems? Do I contribute what’s expected of me, on time and with sufficient quality?

As someone obsessed with achievement, this isn’t an easy paradigm shift. I still fall into the trap of considering myself a failure if things involving others don’t go as expected.

But I’m working on it. And it’s helped me be a bit more compassionate towards myself and others who are trying to do the right thing in a group context.

Mushrooms & Migration

Last night I participated in one of the most interesting panels I’ve ever been in, and I can’t stop thinking about it.

I was invited by WHYY (greater Philadelphia’s public radio station) to participate in a live recording of their flagship news program, Studio2. The location was Kennett Square, PA, commonly known the mushroom capital of the world. If you’ve eaten mushrooms lately, chances are they were grown there. The pitch made by the person who invited me was that we would talk about how immigration is affecting the mushroom industry in Kennett Square.

To be honest, it didn’t seem like that exciting at first. Who cares that much about mushrooms? But I accepted because it seemed like a good opportunity to promote my book.

I wrong not to be excited or interested.

Kennett Square is a perfect microcosm of all the migration issues we’re currently debating at the national and global level. The border. Labor shortages. Economic growth. Investment. Safety. And so much more. (Some background here.) Zooming into the specifics of one industry in one community turned out to be a better way to really understand the issues than speaking about then in generalities.

Part of what made the conversation so interesting is that the panel showcased people with very different priors on the subject. Nancy Ramirez is a local immigration attorney who grew up in Kennett Square as the daughter of a Mexican undocumented immigrant who worked the mushroom farms. Guy Ciarrocchi is the former president of the local Chamber of Commerce, a former congressional candidate for the Republican party, and a Trump supporter. And then there was me.

I invite you to listen to the conversation. It’s airing today (September 5) at noon ET on WHYY. That’s unrealistic for most of you. But never fear. It’ll also show up (in a few hours) as a podcast episode on Studio 2’s website or on your favorite podcast app.

I think you’ll learn a lot. And like me, you’ll be surprised at how much people with differnet political priors have in common when it comes to local issues.

The Eagle & the Quetzal

The other day, I was walking from my office to my car when I came across this van along Locust Walk on the UPenn campus. The flags, along with images of the eagle and the quetzal, were instantly recognizable because I’ve lived in both Guatemala and the US.

I don’t know the owner of this van. But it’s probably a Guatemalan-American (duh!). And it’s clear to me that this person deeply cares about both countries and cultures. This isn’t just a pair of tiny bumper stickers, but something that requires meaningful thought, effort, and expense to put in the back of a work van.

The picture perfectly encapsulates both the fraught debate we have about immigrant assimilation and what the evidence tells us about it.

First, the debate.

As you already know, I speak a lot about the economic benefits of immigration. When I do, it’s very common for people to say something like this: “I’m not sure I want the economic gains from immigration if these foreigners won’t assimilate.” The underlying worry is that newcomers will fail to adopt local values. In large numbers, this might lead to an irrevocable erosion of the precious cultural heritage of the receiving country.

Which raises the perennial question of how aggressive we should be in demanding that immigrants abandon their original language, religion, and values in favor of their local equivalents. Should we expect that Guatemalans abandon the quetzal in favor of the American eagle?

Now, the evidence.

John Berry and his colleagues have been studying this for decades. Their research is widely considered to have produced the canonical model on acculturation, and it can be summarized like this:

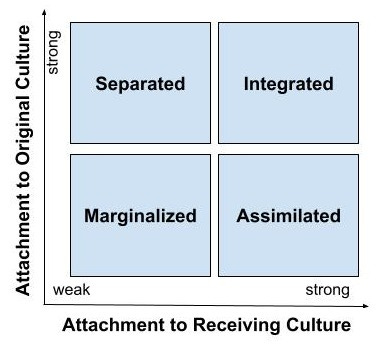

A person who moves from one cultural context to another can inhabit one of four quadrants:

Marginalized: they have weak attachment to both the original and the new culture. This is the definition of an identity crisis.

Separated: they remain strongly attached to their original culture and fail to adopt the new culture. This is the nightmare scenario for those who worry about immigrants threatening the receiving country’s culture.

Assimilated: they abandon their original culture and replace it with the new culture. This is often presented as an ideal scenaior by those who worry about immigrants threatening the receiving country’s culture.

Integrated: they have strong attachment to both the original and the new culture.

We can all agree that the first two are less than ideal. So the debate often comes down to whether it’s better for someone to be assimilated or integrated.

The evidence clearly favors integration over assimilation. For at least two reasons.

The first has to do with the immigrant. Giving up your mother culture is not only really difficult—it’s nearly impossible for first-generation immigrants—but it leads to psychological distress. Immigrants are not happy in this state. Imaging trying to give up certain things you’ve loved and taken for granted since childhood? This is only a realistic expectation (and the most common outcome) for the children or grandchildren of immigrants.

The second reason has to do with the rest of us. Because integrated immigrants are strongly attached to the new culture, we can be confident that they will adopt core values and preserve core institutions—like freedom or the Constitution in the US or liberte, egalite, fraternite in France. But by also reamining attached to their mother culture, immigrants introduce us to new ideas, products, and activities that end up enriching our lives.

Those differences aren’t just nice. They’re essential to produce the economic benefits of which I’ve written about in previous posts (innovation, investment, entrepreneurship) and to keep our own culture vibrant and alive. Like the external inflow that keeps a body of water fresh instead of stagnant.

This is why the van with the eagle and the quetzal is something to be celebrated. It perfectly showcases an integrated immigrant who will preserve what Americans love most about their country today, while bringing something a bit different that will become part of what Americans love most about their country tomorrow.

(If you want to read more about assimilation and integration, I encourage you to check out chapter 7 of my book.)

*****************

Thank you for reading! And be well until next time.

Zeke